Publication - David Leavitt

Visit Manitoga, the House, Studio and Woodland Garden of pioneer industrial designer, Russel Wright (1904-1976). Tour Dragon Rock, Wright’s experimental home which he built onto the rock ledge of an abandoned quarry while masterfully orchestrating the surrounding landscape into a series of outdoor rooms of varying character and delight.

THE ORIGIN OF DRAGON ROCK

David L. Leavitt (1918-2013)

Leavitt, Henshell and Kawaii

Since this is first time everyone connected with the restoration of Dragon Rock has gotten together for a workshop, and since it has now been designated a National Historic Site, I have been asked to say a few words about its inception and Russel Wright's design intent.

Going back a few years to give you some idea of my history, and to explain why both the house and its surroundings have a noticeable Japanese aura about them (especially to artists and designers), I would like to establish the source of this aura, and my contribution to its influence on Russel's design philosophy.

In 1940, when I was preparing to receive my B.A. degree in Architecture at the University of Nebraska, a design teacher who was a graduate of Princeton, suggested I enter the competition for the "Princeton Prize in Architecture". Happily I won the prize, and went on to get my Master's Degree there two years later. During that time I worked each summer with the well-known architect Antonin Raymond at his farm in New Hope, New Jersey not far from Princeton.

Raymond and his wife Noemi had gone with Frank Lloyd Wright to Japan in the twenties to build the Imperial Hotel. He later set up his architectural practice in Tokyo, returning to the U.S. only when World War II threatened. As war began in Europe, we were busy on the farm; with Junzo Yoshimura we designed and built the Montauk House, now owned (and loved) by Ralph Lauren. George Nakashima was there too, starting to make his natural furniture, similar to some of Russel's pieces.

After Pearl Harbor I joined the Navy and was ordered to the Pan American Airways School in Coral Gables to become an Aerial Navigator. Four years later, stationed on Guam, I navigated our skipper to Japan a week or so before MacArthur arrived to sign the treaty.

When the war was over, I rejoined the Raymond and Rado firm in New York, designing many houses, commercial and recreational buildings. In 1950 I got the wanderlust again, entered the Rome Prize competition, won it, and spent the next year and a half at the American Academy in Rome.

In the middle of my second year in Italy, Mr. Raymond sent me a letter stating he had the commission to design the Readers Digest Building in Tokyo, which would be the first modern building in Post-war Japan. He invited me to return to New York to design it, then go with him back to Japan to build it (an invitation not to be refused). Paul Weidlinger proposed an innovative structural system for it, which stood up in an earthquake in spite of Japanese engineers' concerns. It featured a new heat pump for both air-conditioning and heating. To compliment the landscaping Isamu Noguchi created a beautiful sculpture and fountain for it.

After three years in Tokyo, designing all types of buildings, including the US Embassy Housing, the Mikimoto Pearl building on the Ginza plus many churches and houses, I decided to return to New York and set up my own architectural practice. This is where the story of Dragon Rock begins.

During this time Russel had become the famous Industrial Designer. With his wife Mary he had bought acreage above Garrison, adopted little Annie, and used the small farm house, still existing to the west as a summer retreat. Russel was asked by the US Government to go to the Far East to help them make their artistic creations saleable in America. This included a visit to Japan, where the house and gardens were a great revelation to him.

When Mary died, Russel was left with young Annie and a dream to build a house on the Garrison site for the two of them like the ones he had admired in Japan. This is when he spotted my New York apartment published in the New York Times. We had a pleasant interview in my office, where he liked the houses I had designed using Japanese principles, but suitable for modern living. He promptly hired me to design his house realizing he himself could not design the kind of house that he wanted. Being very publicity conscious, he insisted on including a clause in our contract stating, whenever the house is published, I was to be listed as the architect, but he must be listed as the Interior Designer.

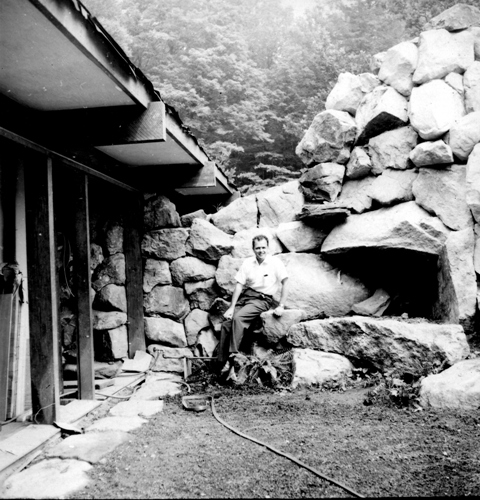

Being very well organized he had already settled on a site for the house, had dammed up the empty quarry to make a swimming pool, and diverted a stream which ran through the site to create a waterfall on the opposite side of the pool. He also had a detailed survey made with one-foot contours and major tree locations.

His program called for a large two-story central living and dining room, a wing for Annie to the west, and his live-in studio plus guest rooms to the east, separated by a pergola.

He vetoed several of my suggestions:

A) to build the house off the ground to keep out moisture-but no, he wanted the house built into the ground.

B) to use sliding anonized aluminum sash on wheels - but no, he wanted oak sash.

C) to handle the drainage provide gutters with Japanese chain style down spouts - but no, he wanted the water to drip off the eaves.

D) he wanted a flat roof covered in vines, and I warned him the roots would cause leaks.

For an architect this was a once-in-a-lifetime dream commission, and I eagerly set to work designing a preliminary layout. A month or so ago, I discovered the original tracing of this rolled up in a closet. (I'm giving a copy of it to the archives). In one corner one can discern Russel's comments or suggestions. It is truly amazing how close this drawing is to the final plan.

With few adjustments Russel wanted in the plan, I made preliminary elevations and a perspective looking up at the house from below. One of Russel's draftsmen built a model and did several interior sketches. Then, with Russel's final approval, my firm Leavitt, Henshell and Kawai, was ready to produce the working drawings. Justin Henshell still has a construction firm in Red Bank, New Jersey and I've lost touch with Tom Kawai. Both of them know Japanese construction as well as I do.

Russel was his own general contractor, and since the house took three or four years to build, he had plenty of time to experiment with interior design and create what he called a "design for living". He came up with all kinds of delightful ideas, unusual lighting, walls of pine needles, plastic panels with leaves, grass, bamboo or other natural materials, and he adopted a Japanese custom of changing décor from one season to the next; in his case from winter to summer. He wanted to use stone both inside and out, importing two Japanese gardeners skilled at moving large boulders about. The column and beam design of the house suited his love of nature and became a perfect framework and inspiration for his interior creations. During supervision, taking photos and often bringing along one or two of my design students at Pratt.

As for the nature trails, which along with the house comprise Manitoga, they got started when I suggested to Russel what a Japanese gardener would do to make them more interesting by adding a variety of experiences and surprises along the way. This first path that he and Joe Chapman created around the quarry, with its bridges, stepping stones, open and closed spaces, fields of moss or flowers, vistas, etc. was a blueprint for all the future trails Russel and Joe spent so many happy hours creating. All of which is perfectly consistent with the design intent and philosophy of the house.

I have brought with me working drawings, details, sketches and progress photos for your perusal, along with some photos of my office work, and will try to answer any questions you may have. Of all my projects, I am most proud of Dragon Rock and I'm glad that Manitoga is determined to restore it to its original state, open for public enjoyment. I'm sure Russel, hovering above, is also pleased.

Excerpts from remarks given by David L. Leavitt, the architect of Dragon Rock on 2/8/03 at the seminar "Case Study: Restoring Russel Wright's Studio."